With the saddening developments in Ukraine, the implication of investment arbitration in the context of armed conflict has become one of the hottest topics in the arbitration community.

On 10 May 2023, the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) hosted a joint conference on armed conflict and investment protection. Fifteen speakers discussed substantive protections in the event of an armed conflict, the defences available to host States and issues related to arbitration procedures.

A speaker first addressed several issues related to investment protection, giving an overview of how investment protection has evolved in situations of armed conflicts over time. By way of example, the speaker commented on the AAPL v. Sri Lanka case, in which the tribunal found that Sri Lanka breached its due diligence obligation. According to that tribunal, Sri Lanka failed to take all reasonable measures to prevent the destruction of a shrimp farm owned by a Hong Kong company.

On the facts, the farm was annihilated by Sri Lanka’s military forces. The foreign investor initiated arbitration under the United Kingdom-Sri Lanka BIT (Hong Kong being at that time a British protectorate). Notwithstanding Sri Lanka’s argument that the farm was being used as a “terrorist facility” by the so-called rebel forces, the ICSID Tribunal ordered the host State to compensate the claimant for the loss of its investment. In particular, the tribunal noted that Sri Lanka “violated its due diligence obligation which requires undertaking all possible measures that could be reasonably expected to prevent the eventual occurrence of killings and property destructions”.

In this respect, would the AAPL v. Sri Lanka decision be different if the harm had not been caused by Sri Lanka forces but by forces of another State?

While no clear-cut answer exists, one recent case brought this question to the fore. In Ukraine, a Qatari company operated the Olvia seaport in the city of Mykolaiv. The Qatari investment was, on several occasions, hit by Russian missiles causing damage to its facilities.

Providing food for thought to the panellists and the audience, the speaker asked what the Qatari investor could do in such a case. Can it claim that Ukraine did not ensure security to that investment? Or can it claim against Russia for causing harm to its investment?

Here again, there is no straightforward answer to this issue.

Type of Protections and Protected Investments in the Context of Armed Conflict

A panel discussed the available remedies to investors in case of armed conflicts. Subsequently, the discussions focused on the types of assets (physical or digital) that may be targeted and the territorial aspect where the sovereignty of the territory of a State is disputed.

The panel first focused on the extended war clauses relating to armed conflicts. These clauses typically include compensation for losses suffered by investors in war situations.

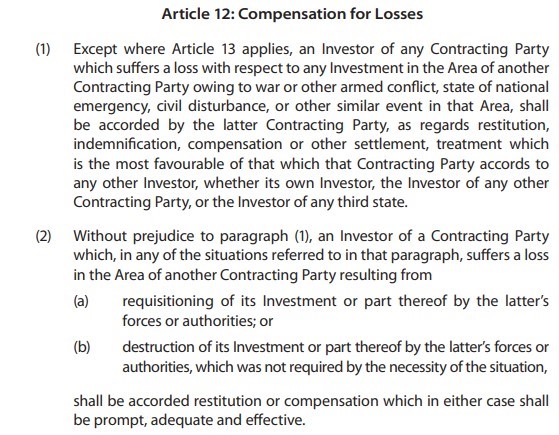

Article 12 of the Energy Charter Treaty is an example of an extended war clause. It reads:

Under extended war clauses, compensation is due only if the disturbance was caused by the host State’s government as opposed to rebel or foreign military forces.

Another oft-cited standard is full protection and security (FPS), which is present in virtually all bilateral investment treaties. While FPS does not explicitly apply to situations of armed conflict, it provides that States must act diligently and defend the foreign investment against violence by third parties in its territory.

In Ampal-American v. Egypt, for example, the tribunal found that the Egyptian authorities failed to protect the claimant’s investment against terrorist attacks and breached the FPS standard.

The panel also analysed the types of assets threatened in war situations: do digital assets fall within the definition of protected investment? The answer depends on the wording of the investment agreement.

The speakers noted that only very few bilateral investments specifically refer to digital assets. While they are not expressly protected, some investment treaties include “intangible assets”, which arguably encompass digital assets.

For example, the Israel-Korea FTA includes the following definition of “investment”:

[I]nvestment means every asset that an investor owns or controls, directly or indirectly, provided that the investment has been made in accordance with the laws and regulations of the Party in whose territory the investment is made, that has the characteristics of an investment, including such characteristics as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk. Forms that an investment may take include:

[…]

other tangible or intangible, movable or immovable property, and related property rights, such as leases, mortgages, liens, and pledges.

Because of the extraterritorial nature of digital assets, the biggest hurdle is to determine the territory on which the harm occurred. While no investment treaty case has specifically explored the territoriality requirement, tribunals are expected to deal with this question soon.

Investment Arbitration Defences in War Situations

The second panel discussed the defences available to States involved in armed conflicts. More specifically, the panel focused on the scope of exceptional or essential security interest (ESI) clauses and state of necessity defences.

ESI clauses are designed to limit the applicability of a treaty where the host State adopts specific measures to protect the national interest. No compensation will be due if a State succeeds in an ESI defence.

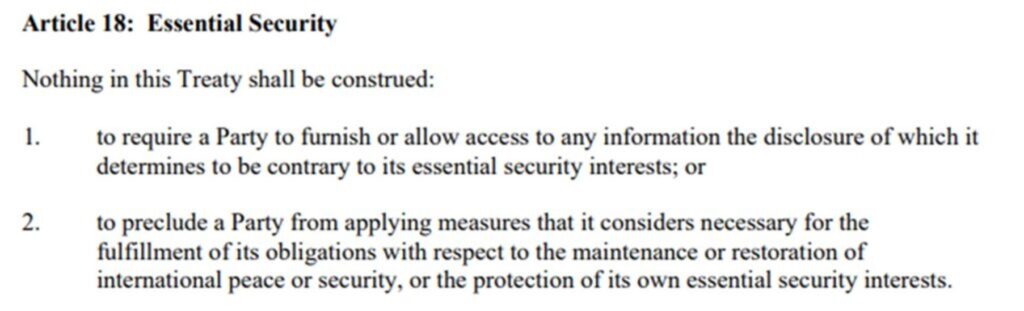

A formulation of ESI is given in Article 18 of the 2012 US Model BIT :

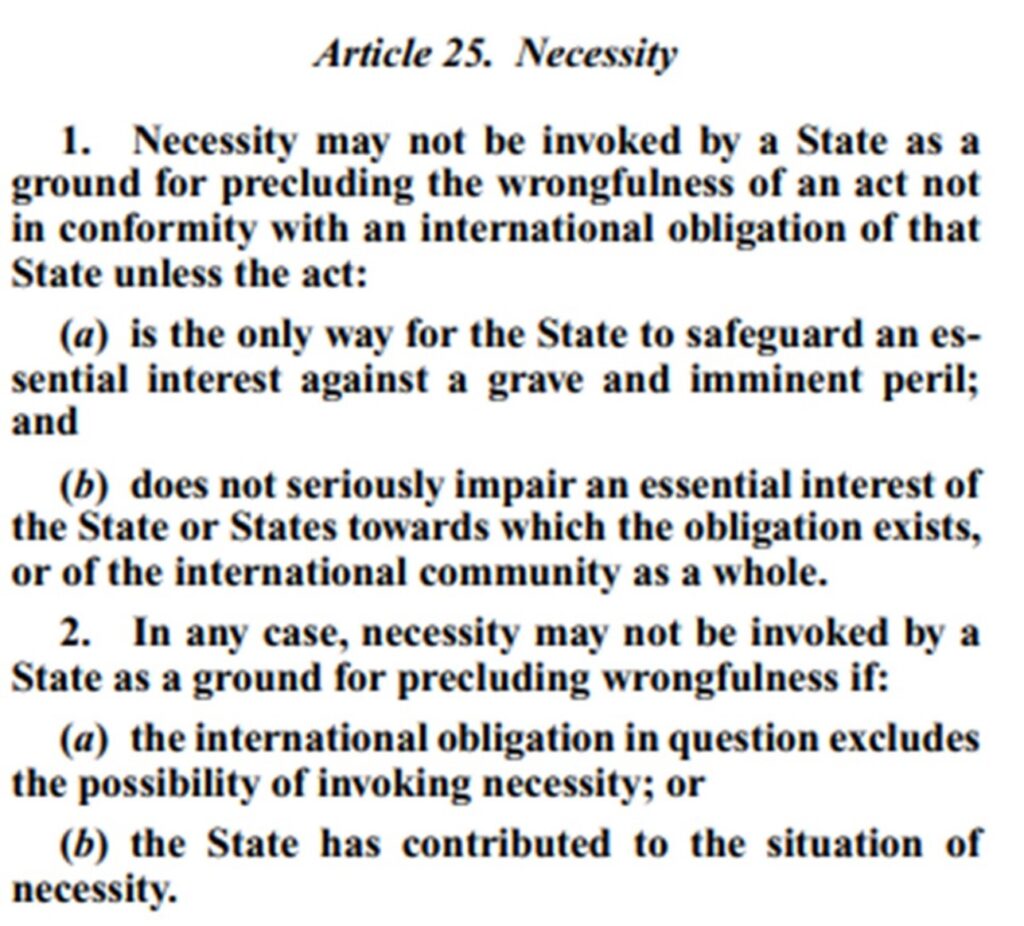

In addition, States frequently rely on state of necessity (or military necessity in case of war) defences provided in Article 25 of the Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts of the International Law Commission:

However, tribunals have reached different conclusions on the scope of necessity in analogous cases. Moreover, reliance on “necessity” is subject to certain limitations outlined in Article 25 of the Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts.

Procedural Issues in Investment Arbitration in the Context of Armed Conflict

The last panel gave an overview of procedural issues that may arise in situations of armed conflict.

The panel highlighted the availability of provisional measures as a valuable tool to preserve evidence and protect the status quo of disputes in war situations, although their applicability may be limited.

The panel also briefly discussed the dilemma of representation in war situations. The panel agreed that tribunals tend to look at the de facto control of States and territories to determine who holds the right to represent a country in situations of armed conflicts.

Additionally, the panel discussed issues relating to enforcement and compensation to foreign investors. In particular, the panel highlighted that as causation for damages may be difficult to establish in case of war, where evidence can be destroyed, tribunals may, in some instances, shift the burden of proof to the respondent State.

Finally, the panel stressed that award creditors should consider the difficulties arising from international sanctions. At the enforcement stage, many national courts will resist enforcement based on international sanctions imposed on some States, as seen in ConocoPhillips’ attempts to enforce its arbitration award against Venezuela in third countries.