Back-to-back clauses are a common feature of large international construction projects, particularly in the infrastructure and energy sectors, where works are delivered through multi-tiered subcontracting structures. In such arrangements, employers and subcontractors have no direct contractual relationship, a separation commonly referred to as the principle of privity of contract.[1]

As a result, this contractual structure can create difficulties when defects, delays, or payment disputes arise across the project chain. To address these challenges, parties rely on back-to-back clauses to align key contractual obligations and risk allocation between the main contract and the subcontracts. When properly drafted, these clauses promote contractual consistency and support the efficient resolution of disputes, including in international construction arbitration.

As a result, this contractual structure can create difficulties when defects, delays, or payment disputes arise across the project chain. To address these challenges, parties rely on back-to-back clauses to align key contractual obligations and risk allocation between the main contract and the subcontracts. When properly drafted, these clauses promote contractual consistency and support the efficient resolution of disputes, including in international construction arbitration.

What Is a Back-to-Back Clause?

A back-to-back clause is commonly regarded as a core contractual provision in construction contracts.[2] It allows the main contractor to transfer downstream the rights, obligations, and risks it assumes under the principal contract by replicating those elements in the subcontract.[3]

Use of Back-to-Back Clauses in Large-Scale Construction Projects

In practice, parties use back-to-back clauses most frequently in large-scale construction projects, including Engineering, Procurement and Construction (“EPC”) contracts. Under the EPC model, the employer appoints a single main contractor responsible for the design, engineering, procurement, and construction of the works, often on a lump-sum basis. The main contractor then relies on back-to-back subcontracting to pass these comprehensive obligations and associated risks to subcontractors.[4]

Standard forms commonly used in international construction practice, including the FIDIC model contracts developed by the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, expressly accommodate this contractual structure.[5]

Practical Implementation and Its Limits

In practice, parties rarely incorporate the head contract in full into the subcontract. The mirroring is commonly implemented by reproducing selected rights, obligations, and remedies of the principal contract in the subcontract. This technique allows the main contractor to align contractual responsibilities across the project chain without granting the subcontractor complete visibility over the terms of the principal contract.[6]

However, replicating individual contractual provisions from one contract to another presents inherent limitations. Where parties fail to replicate a specific right or remedy, that provision remains enforceable only at the upstream level. As a result, gaps in replication may operate against the main contractor or concessionaire.[7]

This risk was illustrated in Chandler Bros Ltd v Boswell.[8] Although the subcontract required the subcontractor to perform the works in accordance with the head contract and incorporated several of its terms, it did not expressly include the contractual power allowing the engineer to order the subcontractor’s removal. When the subcontractor was removed pursuant to the main contract, the court held that the contractor was liable in damages for breach of the subcontract, on the basis that the removal power had not explicitly been incorporated.[9]

The Legal Tightrope: Entitlement to Payment vs. Timing

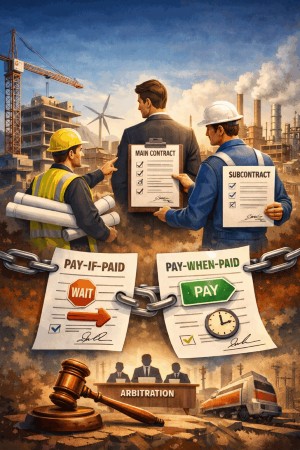

Courts and arbitral tribunals frequently examine the legal effectiveness of back-to-back clauses because these clauses determine which party ultimately bears the financial consequences of a project owner’s refusal to recognise or pay a claim.[10] The key issue is whether a back-to-back clause affects the existence of the payment entitlement itself or merely regulates when payment becomes due.

This distinction, commonly described as pay-if-paid versus pay-when-paid, plays a decisive role in construction arbitration. Importantly, its implications extend beyond payment to variations, extensions of time, and other downstream entitlements.

Entitlement-Based Back-to-Back Clauses (Pay-If-Paid)

Under a strict back-to-back structure, the contractor or subcontractor acquires a right to payment only if the upstream party first receives payment from the project owner.[11] In this configuration, upstream payment operates as a condition precedent to the downstream payment obligation.[12]

From a commercial perspective, this structure protects the main contractor or concessionaire from financing claims that the principal ultimately rejects.[13] Where the contractual wording is clear, arbitral tribunals generally uphold this allocation of risk.

Importantly, this linkage may survive the termination of the principal contract. In Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud, the contractor contested the scope and effects of the back-to-back clause, which provides for an express waiver of claims against the concessionaire beyond amounts recognised and paid upstream.[14] The contractor argued that, following the termination of the EPC Contract, the obligations arising from that clause were extinguished.[15] The tribunal rejected that argument. It held that the back-to-back mechanism, including the agreed waiver, survived the termination of the EPC Contract.[16]

Timing-Based Back-to-Back Clauses (Pay-When-Paid)

By contrast, where the contract does not clearly condition entitlement, tribunals often interpret back-to-back language as regulating only the timing of payment. In such cases, the obligation to pay remains, even if upstream payment is delayed or not received. [17]

Tribunals and courts commonly treat references to receipt of funds, such as payment within a specified period after receipt, as cash-flow mechanisms rather than conditions precedent to entitlement.

The High Court of Delhi adopted this approach in Next Generation Business Powers Systems Ltd v. Telecommunication Consultants India Ltd. The contract referred to a “Guaranteed Revenue Payment” and provided that payment would be released within a week of receipt of payment from the government entity.[18] Reading the payment clause as a whole, the court held that there was no provision stating that payment would not be made if upstream payment was not received.[19] Accordingly, it interpreted the clause as fixing the timeframe for payment, not as conditioning entitlement.[20]

Extension of the Back-to-Back Logic Beyond Payment

Back-to-back clauses do not operate solely in relation to payment. In practice, the same contractual logic is frequently extended to other key rights and obligations within the contractual chain.

In particular, subcontracts frequently link a subcontractor’s entitlement to extensions of time to the relief granted upstream to the main contractor.[21] This structure allows the main contractor to preserve alignment between upstream and downstream schedules.

Moreover, subcontracts commonly impose shorter notice periods, allowing the main contractor to comply with upstream notice requirements that operate as conditions precedent.[22]

Finally, parties may also apply the back-to-back logic to the allocation of liability. In this context, tribunals may distinguish between payment for work actually performed and liability for losses arising from external events. This distinction was illustrated in Ermir v. Biwater, where the sole arbitrator held that, while the contractor’s payment obligations vis-à-vis the subcontractor were not back-to-back, liability for losses caused by the Libyan revolution was contractually aligned with upstream liability. Consequently, compensation for such losses became payable only if, and when, the contractor received corresponding payment from the employer.[23]

Conclusion

Back-to-back clauses play a central role in international construction contracts, but parties can rely on them only when they draft them with precision. Recent case law shows that tribunals actively distinguish between entitlement and timing of payment, as well as between payment obligations and liability for external risks. Accordingly, contractors, concessionaires, and subcontractors should review back-to-back provisions at an early stage. By doing so, they can better manage risk allocation and significantly reduce the likelihood of disputes in construction arbitration.

[1] J. Murdoch et al., Construction Contracts Law and Management (5th edn., 2015), para. 19.3.

[2] See, e.g., Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, para. 112.

[3] Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, para. 118.

[4] Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, para. 117.

[5] See, e.g., The FIDIC Conditions of Subcontract for Construction (1st edn., 2011); C. Chern, Chern on Dispute Boards practice and procedure (3rd edn., 2015), p. 19; Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, para. 117.

[6] G. M. Alvarez et al., International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 63.

[7] G. M. Alvarez et al., International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 63.

[8] Chandler Bros Ltd v. Boswell, 3 All ER 179 (1936) cited in G. M. Alvarez et al., International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 63.

[9] Chandler Bros Ltd v. Boswell, 3 All ER 179 (1936) cited in G. M. Alvarez et al., International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 63.

[10] Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021; Next Generation Business Powers Systems Ltd v. Telecommunication Consultants India Ltd, Judgment of the High Court of Delhi 2025/DHC/302-DB, 21 January 2025.

[11] See, e.g., Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, paras. 112, 159 (“The Parties hereby state for the record that in no case shall the Concessionaire be obliged to acknowledge to the Construction Company any sum of money or right that has not been previously acknowledged to the Concessionaire by the MOP, MINSAL or the competent Courts, as the case may be. In accordance with this principle, the Construction Company waives any claim against the Concessionaire aimed at obtaining payments or compensations that exceed those that were effectively recognized and paid to the Concessionaire by the MOP or MINSAL.”).

[12] M. S. Zicherman, Pay-if-Paid vs. Pay-when-Paid in Construction Contracts, p. 2.

[13] M. S. Zicherman, Pay-if-Paid vs. Pay-when-Paid in Construction Contracts, p. 2.

[14] See, e.g., Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, paras. 112, 159.

[15] Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, para. 42.

[16] Astaldi Sucursal Chile v. Sociedad Concesionara Metropolitana de Salud (Sociedad Concesionaria Metropolitana de Salud v. Astaldi Sucursal Chile), CAM – Santiago Case No. 3584-19 (C-3586-19), Award, 30 December 2021, paras. 143-148.

[17] M. S. Zicherman, Pay-if-Paid vs. Pay-when-Paid in Construction Contracts, p. 1.

[18] Next Generation Business Powers Systems Ltd v. Telecommunication Consultants India Ltd, Judgment of the High Court of Delhi 2025/DHC/302-DB, 21 January 2025, para. 23 (“The TCIL [main contractor] would submit its bill based on the sub-consultant’s quarterly bill to GOG [project owner] within a week, and payment to NGBPSL [subcontractor] shall be released within a week of receipt of TCIL’s payment from GOG.”).

[19] Next Generation Business Powers Systems Ltd v. Telecommunication Consultants India Ltd, Judgment of the High Court of Delhi 2025/DHC/302-DB, 21 January 2025, para. 25.

[20] Next Generation Business Powers Systems Ltd v. Telecommunication Consultants India Ltd, Judgment of the High Court of Delhi 2025/DHC/302-DB, 21 January 2025, para. 23.

[21] G. M. Alvarez et al., International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 65.

[22] C. Chern, Chern on Dispute Boards practice and procedure (3rd edn., 2015), p. 19.

[23] Ermir İnşaat Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. v. Biwater Construction Ltd., ICC Case No. 24710/GR, Final Award, 24 February 2021, paras. 125-135.