Claims for lost overheads and profit are common in construction arbitrations involving delay and disruption. When the completion of the Works in question was caused by the Employer’s delay, Contractors often include a claim for lost contribution to head office overheads and the lost opportunity to earn profit (either on the project which is the subject of the claim or on another project) (see Prolongation Claims in Construction Disputes).[1]

The Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol (2nd Edition, February 2017) (the “SCL Delay Protocol“), prepared by the Society of Construction Law, was designed to provide guidance for determining extensions of time and compensation for delay and disruption in construction disputes. The SCL Delay Protocol is frequently relied upon by international practitioners and adjudicators when dealing with the most common delay and disruption issues that arise in construction disputes, including the need to calculate lost contribution to head office overheads and profit.

Head Office Overheads

The SCL Delay Protocol defines head office overheads as the “incidental costs of running the Contractor’s business as a whole” including “indirect costs which cannot be directly allocated to production, as opposed to direct costs which are the costs of production”.[2] The SCL Delay Protocol explains that head office overheads may include, amongst others, items such as rent, rates, directors’ salaries, pension fund contributions and auditors’ fees.[3] The SCL Delay Protocol further clarifies that in accountancy terms, head office overheads are generally referred to as administrative expenses, whereas the direct costs of production are referred to as costs of sales.[4]

In general, head office overheads may be divided into two categories:[5]

- “dedicated overheads” – costs which can be attributed to specific Employer delay; and

- “unabsorbed overheads” – costs which are incurred by the Contractor regardless of the volume of work, such as for instance, costs of rent and some salaries.[6]

Head office overheads are generally recoverable as a “foreseeable loss” resulting from prolongation unless the specific contract in question, or the applicable law, provides otherwise.[7] It shall be noted that the term used in the SCL Delay Protocol, “head office overheads“, is not necessarily used in all construction contracts. For instance, standard FIDIC Forms of contract use the term “off the Site overhead charges” (FIDIC–4th, Clause 1.1(g)(i), FIDIC–1999, Clause 1.1.4.3) and “Contractor’s general overhead costs” (FIDIC–4th, Clause 52.3).

Lost Profit

Under most standard forms of construction contracts, lost profits are typically not recoverable. Instead, Contractors typically frame their claim for lost profits as a claim for damages for breach of contract.[8] An appropriate rate of profit is often taken from a Contractor’s audited accounts for the previous three financial years. As both overheads and profits are computed using the same set of accounting data, they are normally formulated as the same category of claim.[9]

However, as correctly pointed out by experts and commentators, there are obvious difficulties associated with estimating profits which could have been earned on work which has not been secured. In practice, reference is usually made to past records of profitability, which is, however, merely indicative evidence of a contractor’s capability to earn profits.[10]

Recovery of Overheads and Profit

In order to recover unabsorbed overheads and lost profit, the Contractor must be able to demonstrate:[11]

- that it has failed to recover its overheads and earn the profit it could reasonably have expected during the period of prolongation; and

- that it has been unable to recover such overheads and earn such profit because its resources were tied up by Employer Risk Events.

The SCL Delay Protocol further clarifies that the Contractor must demonstrate that there was other revenue and profit-earning work available which, had it not been for the Employer’s delay, it would have secured.[12] In other words, as one leading commentator on construction law and practice in Singapore explains, to sustain a claim for loss of profit or offsite overheads, a Contractor must first show that “for the critical period of the delay, market conditions in the construction industry were sufficiently favourable at the relevant point in time, so that it is reasonable to expect that the resources which were tied up in the delayed project could have been deployed to earn a profit and to enable him to recover his head office overheads on such work as could be reasonably secured at the material time.”[13] Whether the Contractor will succeed in this essentially depends on if the Contractor can demonstrate that it had reasonable prospects of securing such work.

A problem frequently pointed out by experts, however, is that the profitability of a contractor’s track record is not necessarily conclusive of the profitability of work which a contractor is prevented from undertaking.[14] It should therefore always be remembered that the amount claimed reflects the average profit and overheads contribution achieved in a Contractor’s past projects.

In practice, the Contractor is frequently not able to demonstrate through its records its head office overheads and profit, or it is simply not possible to quantify the unabsorbed overheads and lost profit. In these cases, the Contractor may use one of the three commonly-used formulas to calculate its losses. It should be mentioned that the burden of proving losses almost always lies with the Contractor, as the party claiming them.

The most commonly-used formulas to calculate head office overheads and lost profit are the Hudson, Emden and Eichleay formulas. Further guidance on how to use each of these three formulas is provided in Appendix A to the SCL Delay Protocol. The Society of Construction Law has also provided a useful spreadsheet to assist with using the formulas.

The Hudson Formula for the Calculation of Overheads and Profit

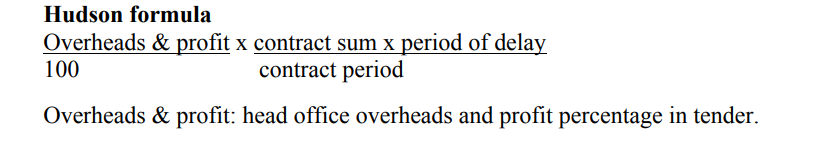

The oldest formula for the calculation of lost overheads and profits is the Hudson formula, first mentioned in Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts.[15] The Hudson formula has been extensively cited, and used, especially in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions. The Hudson formula is constructed in a very simplified manner to calculate overheads and profits as follows:[16]

There are problems with this formula, however, as it is relying on a number of assumptions. The main problem is that the calculation is derived from a number which already contains an element of head office overheads and profits, causing double counting, which cannot be avoided.[17] Another problem is that the formula does not provide any assistance to the determination of the percentage rate for profit and overheads recovery for a particular case. In general, there is a preference for the other two formulas, which are considered as slightly more precise,[18] even though, due to its simplicity, the Hudson formula is still frequently used in practice.

Emden’s Formula for Calculation of Overheads and Profit

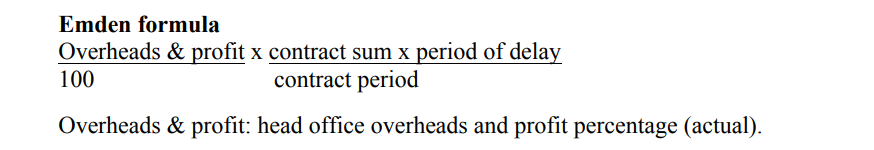

Emden’s formula represents a “variant of Hudson” which, however, “resembles Eichleay”, as certain commentators state.[19] The main difference in comparison to the Hudson formula is that Emden’s formula applies average head office overheads and profits that were achieved elsewhere by the Contractor’s business as a whole:[20]

One problem is, as with the Hudson formula, that it assumes that the average weekly contract turnover anticipated at the outset of the works would remain the same during the period of delay. There is also an inherent problem of double recovery in Emden’s formula as well.[21]

The Eichleay Formula for the Calculation of Overheads and Profit

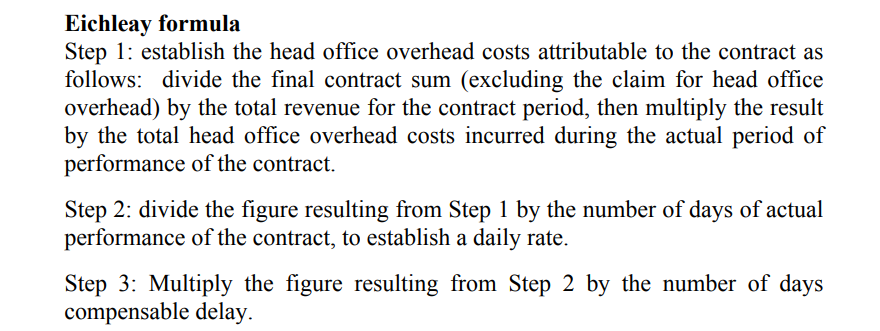

The Eichleay Formula, named after the case where it was used for the first time (Eichleay Corp (Appeal of ASBCA 5138 60-2 BCA 2668 (1960)), is more commonly used in the United States. The Eichleay formula includes an additional step to enable determination of the percentage to be used for fixed overheads contribution:

The Eichleay formula assumes an average weekly turnover that is derived from the final billing for the works in question and the actual, instead of anticipated, period to perform these works.[22] This is its main advantage, as the head office overheads and profits recovery inherent in the contract are not duplicated in the formula result. However, like the Hudson formula, the Eichleay formula assumes that head office overheads are distributed in a consistent manner throughout the contract.

There are conceptual issues with all three formulas, which is why they are frequently criticized by experts as inaccurate or unreliable. In the absence of a better way to calculate lost overheads and profits, however, caused by the Contractor’s lack of sufficient documentation and/or records, the use of all three formulas has been widely accepted in construction disputes around the world.

[1] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.2.

[2] SCL Delay Protocol, Appendix A.

[3] SCL Delay Protocol, Appendix A.

[4] SCL Delay Protocol, Appendix A.

[5] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.3.

[6] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.3.

[7] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.5.

[8] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.4.

[9] Singapore Law and Practice of Construction Contracts, Chow Kok Fong (5th Edn, 2018), para. 10.157.

[10] Singapore Law and Practice of Construction Contracts, Chow Kok Fong (5th Edn, 2018), para. 10.161.

[11] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.6.

[12] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.7.

[13] Singapore Law and Practice of Construction Contracts, Chow Kok Fong (5th Edn, 2018), para. 10.163.

[14] Singapore Law and Practice of Construction Contracts, Chow Kok Fong (5th Edn, 2018), para. 10.163.

[15] Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts (10th Edn, 1970 (Sweet & Maxwell), p 599 and re-stated 13th edition, para 6-070.

[16] SCL Delay Protocol, Appendix A.

[17] SCL Delay Protocol, para. 2.10.

[18] The Sad Truth About Overheads and Profit Claims available at: https://www.adjudication.org/resources/articles/sad-truth-about-overheads-profit-claims

[19] Singapore Law and Practice of Construction Contracts, Chow Kok Fong (5th Edn, 2018), para. 10.184.

[20] SCL Delay Protocol, Appendix A.

[21] The Sad Truth About Overheads and Profit Claims available at: https://www.adjudication.org/resources/articles/sad-truth-about-overheads-profit-claims

[22] The Sad Truth About Overheads and Profit Claims available at: https://www.adjudication.org/resources/articles/sad-truth-about-overheads-profit-claims