Provisional measures can be an effective instrument to protect parties’ rights in arbitration. Although there is no widely accepted definition, provisional measures are, in general terms, remedies or relief whose purpose is to safeguard parties’ rights.

In international arbitration, institutional rules are generally silent as to the standards and principles for the granting of provisional measures. Nonetheless, arbitrators are generally given wide discretion to rule on those standards. In doing so, arbitrators may refer to national laws, for instance, the law of the seat of the arbitration, or the law of enforcement of the award. Arbitration rules and arbitral case law may also provide guidance to arbitrators (for instance, some ICC redacted decisions on provisional measures are publicly available).

Characteristics of Provisional Measures

While the characteristics of provisional measures in international arbitration may vary depending on the applicable laws and procedural rules, there are some basic features, which are listed below:

First, provisional measures require the existence of a dispute. In other words, applications for provisional measures presuppose that a dispute is in place and a final award is expected.

Second, the remedy sought must be provisional or temporary. This means that the measure sought is only needed for a certain period of time, typically until the final award is rendered. It should be noted, however, that provisional measures may take different forms. For instance, Article 35(4) of the Arbitration Rules of the Netherlands Arbitration Institute (NAI) specifies that a decision on a provisional measure may be taken in the form of an order or in the form of an award, which can make a difference as awards are more likely to be enforceable before domestic courts:

Article 35 – Provisional relief in general

4. The decision on the provisional relief may be taken in the form of an order by the arbitral tribunal or in the form of an arbitral award, to which the provisions of Sections Five and Six are applicable. At the request of a party, the arbitral tribunal, having heard the other party or parties, may convert an order by the arbitral tribunal into an arbitral award, in which it shall state the request.

Third, provisional measures may not exceed the final relief or the legal protection sought, as the interim remedy is subordinate to the final relief. In the same vein, there will be no need for interim measures if the final award itself satisfies the parties’ interests at stake.

Fourth, provisional measures should be granted where parties’ rights are at risk until, at least, the issuance of the final award. Such a risk is understood as “urgency”, which is typically seen as a precondition for the granting of provisional relief.

Fifth, the temporary nature of the protection determines that the interim measures may be reviewed and/or modified before the final award is rendered.

Requirements for Provisional Measures in International Arbitration

Generally, for the granting of provisional measures, there must be a strong showing of necessity and urgency. Apart from these two requirements, national legislation and arbitration rules rarely describe in detail the requirements for the granting of arbitral provisional measures.

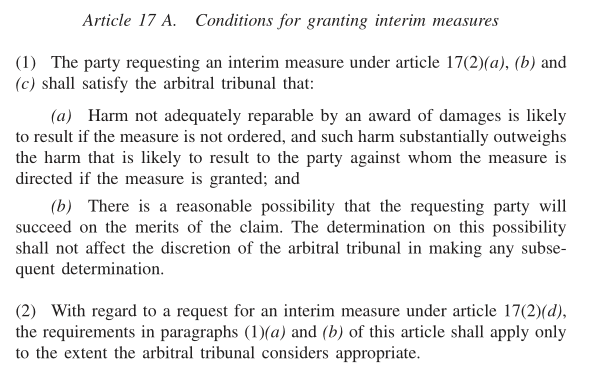

Article 17 A of the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, however, adopts a different approach. It provides that a party seeking interim measures must satisfy the arbitral tribunal that the following conditions exist:

- irreparable harm;

- outweighing possible injury to other parties; and

- a reasonable prospect of success on the merits.

Institutional rules do not typically contain detailed standards for the granting of provisional measures. Typically, arbitral rules will grant the arbitrator(s) wide discretion to award provisional measures, such as “where the tribunal deems necessary” or “under appropriate circumstances”. Indeed, the broad language indicates that provisional measures may be granted in a variety of circumstances. Additionally, the broad language allows arbitrator(s) to rule on the question of “necessity”, which is often paired with the requirement of “urgency”.

In practice, tribunals often require a demonstration of (1) serious or irreparable harm (although some authorities require only a showing of serious harm, without requiring the injury to be “irreparable”); (2) urgency; and (3) no prejudgment of the merits. Some tribunals may require the applicant to establish (4) a prima facie case on the merits.

It is important to note that, in deciding whether to grant a provisional measure, tribunals will bear in mind the nature of the measure sought. For instance, applications requesting the preservation of the status quo or the specific performance of a contract will generally require strong evidence of serious harm, urgency and a prima facie case. On the other hand, provisional measures aiming to preserve evidence, for example, are unlikely to be subject to the same criteria.

Categories of Provisional Measures in International Arbitration

A wide variety of provisional measures are available in international arbitration. Unlike national laws, arbitration rules do not specify the type of provisional measures that may be granted. Generally, arbitral institutions will refer to “any” provisional measure, giving arbitrator(s) broad discretion in determining the appropriate relief.

Due to the consensual nature of arbitration, restrictions may be imposed upon certain types of measures, however. In this respect, arbitrators will not grant measures that are beyond their jurisdiction (e.g., tribunals would be unlikely to grant provisional measures after the final award is issued).

Below is a list of provisional measures that are commonly seen in international arbitration:

- Measures to Preserve Evidence: this type of measure is usually sought when there is a risk that evidence, which one party wishes to rely on, will be harmed, destroyed or lost. The purpose of such a measure is to protect and facilitate the arbitral proceedings.

- Injunctions: injunctions are orders restraining a party from commencing or continuing an action threatening the legal right of another or compelling a party to carry out an act. Arbitrators may grant several forms of injunctions, such as transferring goods to another place, staying a sale of goods, setting up an escrow account, etc.

- Security for Payment: this type of measure aims to advance a payment in order to guarantee the enforcement of the final award. Such a measure requires showing that the applicant has reasonable chances of prevailing in the merits and, if the final award is rendered in its favour, there are strong grounds to believe that the award will not be enforceable.

- Provisional Payment: provisional payments aim to restore, before the final award, a right whose existence is not seriously contested. In reality, provisional payment is not a provisional measure per se since the arbitral tribunal needs to consider whether the requesting party is entitled to a certain amount of money prior to the final decision. Thus, provisional payment is rather an interim remedy, which may be revoked or amended with the final award.

Interim Measures Ordered by National Courts in Support of Arbitration

Arbitrators are not the only authorities entitled to grant provisional measures related to arbitral proceedings. National courts have concurrent power to grant provisional measures in connection with arbitral disputes. In some cases, national courts are the only realistic option for an interim relief, as national courts have powers that go beyond those of arbitral tribunals and arbitral tribunals cannot order interim measures before they exist.

Until the constitution of the arbitral tribunal, there is clearly no possibility of obtaining a provisional measure from it. Despite the efforts of some arbitral institutions to provide pre-arbitral mechanisms,[1] several institutions do not offer such a venue for provisional measures. Additionally, where the provisional measure at stake involves third parties, arbitrators are practically unable to provide effective relief, as they lack jurisdiction over third parties. Consequently, parties in need of urgent relief prior to the formation of the arbitral tribunal typically seek the assistance of national courts.

This concurrent authority is provided for in most national legislations, absent agreement to the contrary. The UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration is a representative example: Article 17J provides that national courts have the same power as arbitral tribunals to issue interim measures:

Article 17 J. Court-ordered interim measures

A court shall have the same power of issuing an interim measure in relation to arbitration proceedings, irrespective of whether their place is in the territory of this State, as it has in relation to proceedings in courts. The court shall exercise such power in accordance with its own procedures in consideration of the specific features of international arbitration.

In the same vein, the Swiss Law on Private International Law recognizes, albeit less expressly, the assistance of national courts in supporting arbitral tribunals, unless otherwise agreed by the parties:

Art. 185

If any further assistance by a state court is required, the court at the seat of the arbitral tribunal has jurisdiction.

In some countries, the circumstances allowing national courts to issue provisional measures are limited. Section 44 of 1996 English Arbitration Act specifies that English courts are allowed to order interim relief in the case of urgency or where the arbitral tribunal is unable to act (e.g., the taking of evidence of witnesses, the preservation of evidence, amongst others). If a request is not “urgent”, the court may only grant provisional measures with the permission of the tribunal or by agreement of the parties.

With respect to institutional rules, Article 28(2) of the 2021 ICC Arbitration Rules provides that parties may apply to any competent national court seeking provisional measures either before the case is transmitted to the tribunal or “in appropriate circumstances even thereafter”. The ICC Arbitration Rules go further and specify that any application to a judicial authority for provisional measures “shall not be deemed to be an infringement or a waiver of the arbitration agreement and shall not affect the relevant powers reserved to the arbitral tribunal” (Article 28(2)).

The 2020 LCIA Arbitration Rules, in turn, indicate that applications for interim or conservatory measures in national courts are allowed “before the formation of the Arbitral Tribunal” and “after the formation of the Arbitral Tribunal, in exceptional cases and with the Arbitral Tribunal’s authorisation, until the final award” (Article 25.3).

The majority of arbitration laws provide that an application for interim or provisional remedies before domestic courts does not amount to a waiver of a party’s right to arbitrate. Likewise, most institutional rules provide that an application for provisional measures before national courts does not necessarily waive parties’ rights under an arbitration agreement, although parties are generally free to exclude court orders for provisional measures if they so wish.

[1] See e.g., the 2012 ICC Pre-Arbitral Referee Rules