Many variables can influence the costs of investment arbitration. While the costs of parties’ counsel and the arbitral tribunal’s fees are far from trivial, other potential variables may be useful to assess and forecast the costs of investment arbitration disputes. In this post, we will explore how some variables may impact the parties’ overall costs in investment arbitration disputes based on scholarly findings.[1]

Cost Nexus in Investment Arbitration

Link Between Parties’ Legal Costs and Tribunals’ Expenses

Research findings revealed that there were strong links between the parties’ legal expenses and the overall tribunals’ costs.[2] This position is perhaps supported by the fact that whenever lawyers spend a significant amount of time and effort in complex cases, tribunals are likely to spend commensurate levels of energy.[3]

Correlation is not causation, however. Legal fees, especially when charged on an hourly basis, may escalate for a variety of reasons, such as difficulty in obtaining underlying documents, poor translation of evidence and expert reports, or lack of expertise in managing investment arbitration disputes in an efficient fashion.[4]

Yet, it is a relationship that it is worth considering when instructing a legal team for investment arbitration disputes.

Link Between Costs and Amounts Claimed

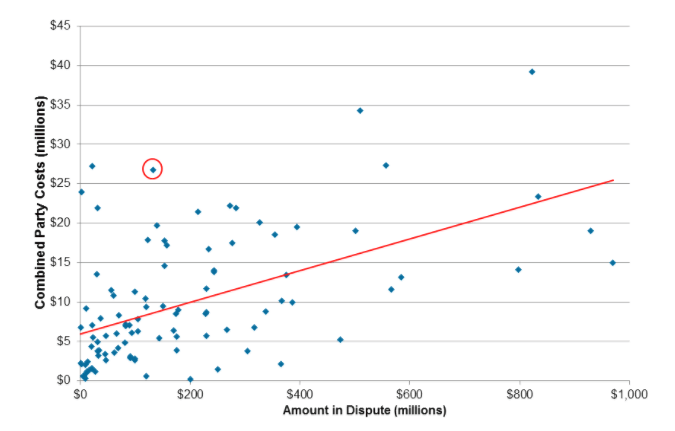

There are reasons to believe that a relationship between counsel costs and the amount claimed exists. Theoretically, legal costs will be higher when higher amounts are claimed to ensure that the value of the claim justifies the expenditures on legal fees. Nevertheless, some tests suggest that there is no reliable connection between the parties’ legal costs and the amounts claimed.[5]

On the other hand, tribunals were likely to spend more time and energy when higher amounts were at stake. While it could be argued that tribunals should resolve the dispute based on the complexity of the case regardless the amount claimed, some research findings showed that as the size of the claim grew, so did the costs of the arbitral tribunal.[6]

This may be attributable to the fact that arbitrators are generally more expert in law than accounting and may need an extensive number of hours to fully assess complex financial models of quantum evaluation reports.[7]

Link Between Costs and the Outcome of the Dispute

It has been suggested that where investors prevailed, they were inclined to pay more for legal fees.[8]

Interestingly, some tests suggested that legal fees were considerably more expensive where investors won, whereas they were less expensive where States defeated the claim.[9] The same study revealed that for cases where the investor prevailed, the claimant’s counsel charged virtually twice as much, while for cases where the State won, claimant’s counsel spent around half the amount that the respondent’s counsel charged.[10]

Tribunals’ costs seemed to remain the same independently from the outcome, meaning that there appears to be no real link between the tribunals’ costs and the prevailing party.[11]

It should be noted, however, that spending more money on counsel does not guarantee favorable outcomes. Rather, the expertise and experience of parties’ legal representatives are more likely to impact the outcome of the dispute.[12]

* * *

All in all, research findings showed that tribunals’ costs were closely related to counsel costs: where parties’ legal costs increased, tribunals’ costs also steadily grew; and, where parties’ legal costs decreased, so did the tribunals’ fees.

Second, the parties’ legal costs seemed to be unrelated to the amounts claimed, while arbitral tribunals’ costs were more closely related to the amounts sought.

Third, outcome may sometimes impact, but not always, the costs of investment arbitration disputes. For claimants, spending more on counsel fees may be correlated to a victory, although this does not mean that the investor will necessarily recover damages. On the other hand, for State respondents, paying more for their counsel did not mean that they were more likely to win or lose the dispute.

Potential Cost Drivers in Investment Arbitration

Costs Related to Arbitral Institutions

There have been many debates on the most expensive venues for arbitration.

While there is still little rigorous research to compare cost variations between institutional and ad hoc arbitrations, investment arbitration disputes tend to be complex. Hence, the absence of an institution controlling the arbitrators’ fees and providing certain facilities will likely affect the overall costs.

Nevertheless, one finding suggested that parties’ legal fees did cost roughly the same, regardless of whether the arbitration was ad hoc or institutional.[13]

With respect to the tribunals’ fees, it did not appear that ad hoc costs were significantly higher than institutional arbitrations, although some tests revealed that SCC tribunals, charging in function of the amount in dispute (see SCC Arbitration Rules, Appendix IV: Schedule of Costs), were the least expensive, whereas ICSID tribunals, charging on an hourly basis (see ICSID Memorandum on the Fees and Expenses), were less expensive than ad hoc tribunals.[14]

Costs Related to Bifurcated Proceedings in Investment Arbitration

Whereas bifurcation is an opportunity to save time and costs, if it is inefficient it will merely increase costs. Some tests suggested that bifurcation was often related to higher arbitration costs, although the main factor driving costs was the length of the arbitration rather than the bifurcation itself.[15]

On the investor’s side, as one may surmise, legal fees were higher in bifurcated proceedings, although the difference became less significant where the parties managed to control the length of the case.[16]

Tribunals’ fees and expenses, in turn, were likely to increase sharply in bifurcated proceedings. Some tests suggested that tribunals in non-bifurcated proceedings charged 50% less as compared to tribunals in bifurcated arbitrations. This might be explained by the fact that ICSID tribunals are paid on an hourly basis; thus, it is reasonable to presume that costs will increase when bifurcation is granted.[17]

For States’ legal fees, the tests did not identify any correlation between higher legal costs and bifurcated proceedings.[18]

In light of the above, parties, counsel, and tribunals should balance the potential prolongation of the case against the lack of certainty in saving costs when considering bifurcation.[19]

Dissenting Opinions

The process of drafting an award is time consuming. Drafting multiple separate opinions will augment the hours spent by the arbitrators. However, when it comes to costs, separate opinions seemed to make little difference, except for States.[20]

While lawyers are not involved in the deliberations, let alone in the drafting of the awards, some tests showed that States’ legal costs increased considerably when separate opinions were issued.

Therefore, State respondents may spend less in legal costs when the final decision is unanimous.[21] Arguably, States may be predisposed to spend more in legal fees when it is warranted by the merits.

Counsel Experience

The tests concerning counsel experience revealed that there was a strong link between the expertise of a claimant’s legal team and legal costs. Some tests suggested that the average legal costs for investors was 200% higher when using highly experienced lawyers.[22]

The legal costs for respondents did not follow the same pattern, however. Thus, the tests did not support that States paid more or less when represented by experienced legal teams.[23]

* * *

While arbitration practice requires a case-by-case analysis, predicting costs in investment arbitration remains an arduous task. This post attempted to summarize potential cost drivers of investment arbitration disputes that should be weighed by the parties and their counsel.

[1] S. Franck, Arbitration Costs: Myths and Realities in Investment Treaty Arbitration (2019).

[2] Id., p. 254.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Id., p. 255.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Id., p. 267.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Id., p. 259.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Id., p. 270.

[14] Id., pp. 270-272.

[15] Id., p. 277.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Id., p. 278.

[20] Id., p. 182.

[21] Id., p. 284

[22] Id., pp. 285-286.

[23] Ibid.