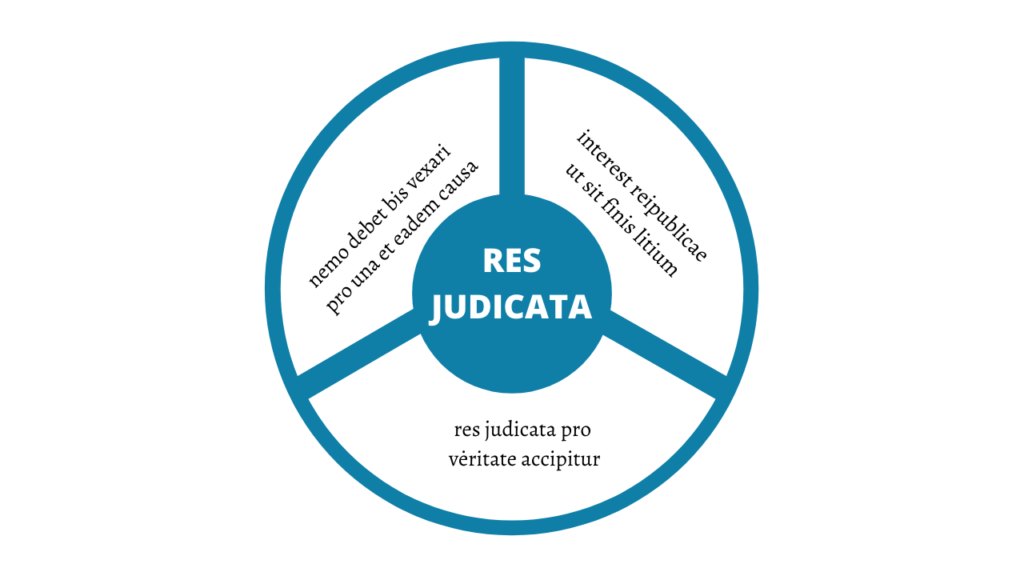

Res judicata implies that a previous and final judgment is conclusive in subsequent proceedings involving the same (i) parties, (ii) subject matter and (iii) legal grounds, which is also referred to as the “triple-identity criteria”.[1]

The principle of res judicata is a general principle of law known both to international law and local law.[2] Like judgments from local courts, international arbitral awards are considered to be final and binding.

Generally, arbitral tribunals have to decide on the res judicata effect of a prior court decision. However, res judicata issues can also emerge between arbitral awards rendered by different arbitral tribunals.

An arbitral award is a decision that will be considered as res judicata in any subsequent proceedings that the same parties may attempt to bring against each other. It is considered as final because the original decision is final and binding upon the parties.

In other terms, res judicata implies that the subject matter of a judgment cannot be relitigated as a judgment is final and binding between the parties, subject to any available appeal or challenge.

When dealing with res judicata, arbitral tribunals rely on one of the following approaches:

- The Common Law approach which allows several res judicata pleas (a plea of cause of action estoppel,[3] issue estoppel,[4] former recovery,[5] or abuse of process[6]); and

- The Civil Law approach which allows only one plea. In France, for example, the doctrine of res judicata is referred to as the “autorité de la chose jugée” (authority of the thing ruled upon), i.e., no recourse against a judgment is possible.[7]

Investment arbitral tribunals and international commercial tribunals have chosen different approaches in applying the res judicata principle.

Res Judicata in Investment Treaty Arbitration

It appears that investment tribunals tend to apply the common law approach to decide on the res judicata effect of prior arbitral awards.

For instance, the tribunal in Amco Asia Corporation and others v. Republic of Indonesia[8] considered that if an ad hoc committee decides to annul only part of the award, the parts of the award that are not annulled are res judicata between the parties:[9]

It is by no means clear that the basic trend in international law is to accept reasoning, preliminary or incidental determinations as part of what constitutes res judicata. The finding of the Pious Fund Case Hague Court Reports (1916) 1, cannot be read in that way, for the Tribunal said only that “all the parts of the judgment enlighten and mutually supplement each other and…all serve to render precise the meaning and the bearing of the dispositif (decisory part of the judgment) and to determine the points upon which there is res judicata…” Had the Decision of the Ad Hoc Committee as to what was and was not annulled (and as to what thus was and was not judicata in the Award) been unclear, all the points in the Decision would undoubtedly have to be relied on to interpret and clarify the dispositif. But the Decision is clear.

Similarly, the arbitral tribunal, in Rachel S. Grynberg, Stephen M. Grynberg, Miriam Z. Grynberg and RSM Production Company v. Grenada dealt with issue estoppel and considered that “[c]ollateral estoppel, it is said, is well established as a general principle of law applicable in international courts and tribunals being a species of res judicata.”[10] The tribunal, citing Amco II, recalled that the res judicata principle is as follows:[11]

[A] right, question or fact distinctly put in issue and distinctly determined by a court of competent jurisdiction as a ground of recovery, cannot be disputed.

It shall be noted that issue estoppel implies that the same question was decided, there was a final decision and the same parties, but no identity of cause. The arbitral tribunal, citing the United States Supreme Court in Southern Pacific Railroad Co v United States, found that findings of a prior tribunal on a series of rights, questions and fact bound the new tribunal: [12]

The general principle announced in numerous cases is that a right, question, or fact distinctly put in issue, and directly determined by a court of competent jurisdiction as a ground of recovery cannot be disputed in a subsequent suit between the same parties or their privies, and, even if the second suit is for a different cause of action, the right, question, or fact once so determined must, as between the same parties or their privies, be taken as conclusively established so long as the judgment in the first suit remains unmodified.

Other international investment tribunals have applied a civil law approach to res judicata, such as the one in Gavazzi v. Romania. In this case, according to the arbitral tribunal, it applied the triple identity criteria to consider that there was no res judicata because of Respondent’s court judgments:[13]

Under international law, three conditions need to be fulfilled for a decision to have binding effect in later proceedings: namely, that in both instances, the object of the claim, the cause of action, and the parties are identical.

Res Judicata in Commercial Arbitration

Because the interpretation of the doctrine of res judicata differs from States to State, commercial arbitral tribunals may apply different national laws to determine res judicata issues.

Certain arbitral tribunals have applied the law of the place where a prior award was rendered. In an ICC award rendered in 1994, the arbitrator applied the law of the place where a prior arbitral award was made. The case involved a tripartite cooperation contract subject to English law for the establishment of an industrial enterprise in Iran. The bank loans to this company were guaranteed by two of the parties to the contract. The first arbitration with its seat in Switzerland, initiated by an Iranian party, resulted in the condemnation of the two other contracting parties to pay him interest on the amount of the guarantee. The Iranian citizen then initiated a second arbitration, but against only one of the other two parties, claiming the reimbursement the principal amount of the guarantee. The arbitrator applied Swiss law to rule on the issue of res judicata.[14]

Other tribunals have referred to the law governing the merits of the dispute because the issue of res judicata was substantive and not procedural.[15]

The law of the place where a new claim is brought has also been chosen by tribunals. For instance, an ICC tribunal having its seat in Paris applied French procedural law while the previous ICC award was rendered by a tribunal seating in Geneva.[16]

Conclusion

International disputes are becoming more complex, involving multiple proceedings which means that more arbitral tribunals will have to rule on res judicata issues. This may increase the number of international awards with inconsistent outcomes, especially in international commercial arbitration.

[1] Interpretation of Judgments Nos. 7 and 8 (Factory at Chorzów), Dissenting Opinion by M. Anzilotti, 16 December 1927), P.C.I.J. (Ser. A) No. 13, p. 23.

[2] R. David, L’Arbitrage dans le commerce international (1982), para. 339.

[3] See e.g., Zurich v Hayward [2017] AC 142.

[4] See e.g., Thoday v Thoday [1964] P 181.

[5] See e.g., Conquer v Boot [1928] 2 KB 336.

[6] See e.g., Henderson v Henderson (1843) 3 Hare 100.

[7] Article 1355 of the French Civil Code which reads as follows: “The authority of res judicata applies only with respect to the subject-matter of the judgment. The subject-matter of the claim must be the same; the claim must have the same ground; the claim must be between the same parties, and brought by and against them in the same capacity.”

[8] Amco Asia Corporation and others v. Republic of Indonesia, ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1, Award in Resubmitted Proceeding dated 5 June 1990.

[9] Amco Asia Corporation and others v. Republic of Indonesia, ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1, Award in Resubmitted Proceeding dated 5 June 1990, para. 32

[10] Rachel S. Grynberg, Stephen M. Grynberg, Miriam Z. Grynberg and RSM Production Company v. Grenada, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/6, Award, 10 December 2010, para. 4.6.5.

[11] Rachel S. Grynberg, Stephen M. Grynberg, Miriam Z. Grynberg and RSM Production Company v. Grenada, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/6, Award, 10 December 2010, para. 4.6.6; Amco Asia Corporation v Republic of Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1), Resubmitted Case, Decision on Jurisdiction, 10 May 1988, para. 30.

[12] Rachel S. Grynberg, Stephen M. Grynberg, Miriam Z. Grynberg and RSM Production Company v. Grenada, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/6, Award, 10 December 2010, para. 7.1.3; Southern Pacific Railroad Co v United States, 168U.S.1, 48-49 (1897).

[13] Marco Gavazzi and Stefano Gavazzi v. Romania, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/25, Decision on Jurisdiction, admissibility and Liability, 21 April 2015, paras. 163 to 174, spec. para. 166.

[14] ICC Case No. 7438, Award (1994), discussed in D. Hascher, L’Autorité de la Chose Jugée des Sentences Arbitrales, p. 22.

[15] ICC Case No. 6293 (1990), award reported in D. Hascher, L’Autorité de la Chose Jugée des Sentences Arbitrales, p. 20.

[16] ICC Case No. 5901, Award (1989).