Energy projects are usually long, complex and require a substantial level of capital. Additionally, the sector has significant exposure to geological events, political changes and environmental regulations. For these reasons, disputes are common in the energy sector, and arbitration has become the preferred method of resolving these disputes, particularly at the international level.[1]

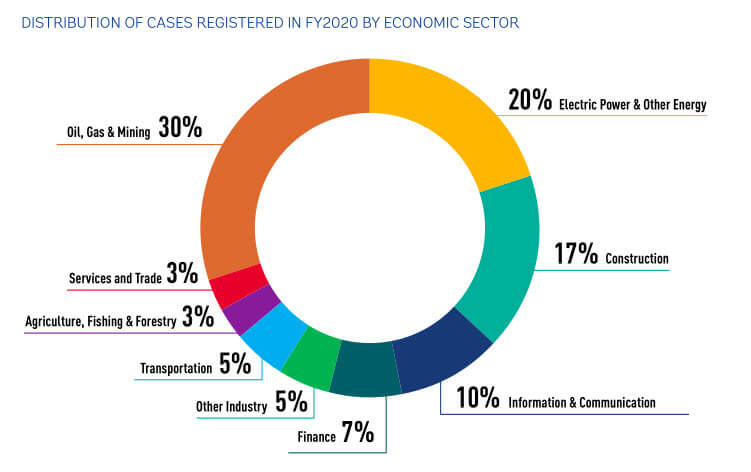

As noted by the 2020 ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics, the energy sector historically generates a significant number of ICC cases.[2] In 2020, the ICC registered 167 new cases related to the energy industry.[3] In the realm of investor-State disputes, the energy sector is also prominent. The 2020 Annual Report issued by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) shows that the energy sector continues to dominate its caseload.[4]

A) The Energy Sector

1) Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy

When it comes to major energy projects, different sources of energy can be used. Generally, these sources fall into two categories: “non-renewable” and “renewable” energy.[5]

Non-renewable energy is the energy that, once used, cannot be reused. It is largely formed by fossils of animals and plants. Examples of non-renewable energy are oil and natural gas. Renewable energy, in turn, derives from geophysical and biological sources that are continually replenished. This is the case of solar, wind and hydro energy.[6]

2) Upstream and Downstream Companies

Companies involved in the energy sector are normally located in the “upstream” or “downstream” segments of the supply chain.[7] These two segments represent the main activities of the energy sector, namely, (1) exploration, (2) production, (3) refining and (4) distribution and selling.

In the sector of non-renewable energy, upstream companies are mostly involved in the extraction of raw materials.[8] At this stage, joint operating and drilling agreements between investors and States are commonly seen.[9] The downstream sector of non-renewable energy covers all operations following the production phase up to the end-user (e.g., refining, processing, distributing, etc.).[10]

In the segment of renewable energy, upstream companies are often involved in research and development, whereas downstream players are largely involved in selling and distribution to the end-user.[11]

So-called “midstream” may also be used to refer to transportation and storage of energy.[12]

B) Disputes in the Energy Sector Using Arbitration

1) Categories of Disputes Involving Arbitration

Energy disputes may fall into different categories depending on the parties involved. Two categories are, however, commonly seen: disputes between States (including State entities) and private parties, and disputes between private parties.

a) Investor-State Disputes

The energy sector is, historically, highly regulated. For years, States and State-owned companies had a monopoly over the extraction and the supply of energy. While new opportunities emerged through privatization programmes, States still maintain a significant degree of involvement in energy projects. The close interaction between the private and public sectors often generates disputes, particularly in capital-importing countries.

The legal basis for such disputes may vary, as indicated below:

- contract-based disputes: private companies in the energy sector will frequently enter into agreements with the State itself or companies owned or controlled by the State. For instance, oil and gas contracts will often be entered with a State or a national oil company (NOC) involved in the exploration, production and distribution of oil and gas. These agreements frequently contain an arbitration clause referring future disputes to arbitration. In this regard, arbitrations stemming from energy contracts entered into with States are not too different from purely commercial arbitrations between private parties, unless the contract itself allows for investor-State arbitration.[13]

- treaty-based disputes: these treaties may take the form of bilateral or multilateral investment treaties, providing for a unilateral offer from the sovereign States to arbitrate in the event of certain classes of disputes.[14] The investor accepts the State’s offer by filing a request for arbitration. In Venezuela Holdings, B.V. v. Venezuela (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/27), for instance, the claimants brought an arbitration under the Netherlands-Venezuela BIT[15] for expropriation and violation of fair and equitable treatment following the implementation of measures that affected the production and export in two energy projects. Examples of multilateral investment treaties are the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) and the now-defunct NAFTA.[16] In past decades, some European countries have faced numerous claims under the ECT. Spain, for instance, has been a party to the most ECT arbitrations in the renewable sector.[17] A number of investors in the photovoltaic industry brought claims against Spain claiming, amongst other things, compensation for indirect expropriation following a series regulatory measures[18] (see, e.g., Isolux Netherlands, B.V. v. Kingdom of Spain (SCC Case V2013/153); Charanne, B.V. et al. v. Spain (SCC Case No. V 062/2012); Eiser Infrastructure Ltd et al. v. Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36); Masdar Solar & Wind Cooperatief U.A. v. Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/1)).

- domestic investment law-based disputes: another legal basis for claims in the energy sector derives from the domestic legislation of host States. Domestic laws and codes that aim to incentive and encourage foreign investments may provide for unilateral consent by the host State to arbitrate. Investors’ consent, in turn, can normally be expressed by way of a written communication addressed to the State or by filing a request for arbitration. Different from treaty-based disputes, the offer to arbitrate in domestic legislations is not always subject to the nationality criterion.[19]

b) Private Disputes

The majority of energy disputes involve private companies, however. Generally, these disputes arise out of a wide range of transactions. If private disputes can be solved by arbitration, they will fall into the overall heading of commercial arbitration grounded in contracts.[20]

2) Common Energy Disputes Suited to Arbitration

- joint venture (JV) and joint venture operating agreement (JOA) disputes: in the energy industry, multi-contract transactions, in particular JV’s and JOA’s, are commonplace. JV agreements are an effective tool to allocate risks, increase capital and share expertise for the development of energy projects. A JOA is a common type of JV agreement. Through JOA’s, parties can designate an operator, a joint operating committee, as well as the commercial and technical framework of the project.[21] Common disputes in JOA’s may stem from the required standard of care owed by the operator and non-operator participants.[22] “Deadlocks” may also occur in 50:50 joint ventures. Further, failures to make cash calls in a timely manner, when requested by the operator partner, may have serious consequences for the defaulting party and, in such cases, arbitration can be expected.[23]

- gas price review: while in typical commercial arbitration, the arbitral tribunal is asked to determine which party is liable and order compensation, in disputes involving gas price review, the arbitral tribunal must determine whether the requirements for a price adjustment have been fulfilled and, if so, to determine the price adjustment. In such disputes, arbitrators must understand, at least, the basic principles of the gas market, although expert evidence is often adduced.[24]

- engineering & construction: disputes may also arise in the context of construction of energy infrastructure. Construction disputes may arise on a purely commercial level or may involve State entities. In these disputes, arbitrators are frequently confronted with issues related to defective items and delays.[25]

- State measures: as mentioned above, States are often involved in disputes in the energy sector. The regulation of rates and services conditions are frequently at the heart of energy disputes. Additionally, interferences of host States in energy projects may lessen its value and give rise to claims of indirect expropriation.[26]

- international boundary disputes between States: this is a very particular type of dispute since it involves sovereign States. These disputes are usually related to oil and gas fields in maritime waters and access to resources in oceanic areas. Typically, the issues that arise in international boundary disputes concern the location of maritime boards and zones of exploration.[27]

- disputes with third parties: in addition to disputes between the main stakeholders, disputes with third parties may also arise. Commonly, these disputes involve services providers, suppliers and subcontractors in JV agreements.[28]

C) Challenges of Arbitration in the Energy Sector

Unsurprisingly, arbitration is the preferred method of dispute resolution in the energy industry. The advantages of arbitration include, among others, party autonomy, access to a neutral forum, flexibility, confidentiality, the ability to choose arbitrators with the required expertise and the enforceability of arbitral awards worldwide.

The particularities of the energy industry may create some procedural challenges in arbitration proceedings, however. A common issue is the consolidation of multi-party transactions in complex construction contracts and JV agreements. In such cases, multiple arbitrations, involving the same or similar facts and legal issues, may be commenced. Once different arbitrations have been commenced, it can be challenging for arbitrators to consolidate multiple arbitrations absent the consent of the parties involved.[29]

In this respect, many arbitral institutions have introduced procedures for consolidation. Nevertheless, many institutions still provide for imperfect procedures, which can be ineffective in real-world circumstances[30] (for more information on commencing an arbitration under several arbitration agreements, see Initiating Arbitrations Under Multiple Arbitration Agreements).

Another procedural challenge, especially relevant in disputes involving JV’s, is the question of arbitrability. While many claims involving JV’s may be remedied by monetary damages, claims involving JV’s deadlocks, change of control or parties’ insolvency may put into question the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. Sometimes the arbitral tribunal may be called upon to terminate the partnership in the JV or to order specific performance to the parties involved.[31]

Issues may also arise in arbitrations involving price review, for which experts are often needed. Expert determination and arbitration clauses can be ambiguous, creating difficulties as to the scope of the arbitral tribunal’s and the expert’s powers.[32]

[1] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1278.

[2] According to the ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics, the energy and construction sectors account for approximately 38% of all ICC cases. See ICC Dispute Resolution 2020 Statistics, p. 17.

[3] ICC Dispute Resolution 2020 Statistics, p. 17.

[4] 2020 ICSID Annual Report, p. 25.

[5] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1280.

[6] Ibid.

[7] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1282.

[8] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1281.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), pp. 1284-1285.

[14] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1286.

[15] The Netherlands-Venezuela BIT was officially terminated on 1 November 2008, see International Investment Agreements Navigator – UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub.

[16] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1288.

[17] J. Adam, Renewable Energy in G. Alvarez, M. Riofrio Piché, et al. (eds.), International Arbitration in Latin America: Energy and Natural Resources Disputes (2021), p. 168

[18] M. W. Friedman, D. W. Prager, I. C. Popova, Expropriation and Nationalisation in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), p. 25.

[19] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1289.

[20] Ibid.

[21] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1293.

[22] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1294.

[23] M. Beeley and S. Stockley, Upstream Oil and Gas Disputes in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), p. 192; S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1293.

[24] M. Levy, Gas Price Review Arbitrations: Certain Distinctive Characteristics in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), pp. 210-211.

[25] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1297.

[26] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1298.

[27] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1282.

[28] M. Beeley and S. Stockley, Upstream Oil and Gas Disputes, in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), p. 194.

[29] G. Vlavianos and V. Pappas, Consolidation of International Commercial Arbitral Proceedings in the Energy Sector in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), p. 244.

[30] G. Vlavianos and V. Pappas, Consolidation of International Commercial Arbitral Proceedings in the Energy Sector in J. W. Rowley QC, D. Bishop and G. Kaiser (eds.), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (2019), p. 246.

[31] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1294.

[32] S. Vorburger and A. Petti, Arbitrating Energy Disputes in M. Arroyo (ed.), Arbitration in Switzerland: The Practitioner’s Guide (2018), p. 1297.