The 2010 UNCITRAL Rules (the “Rules”) provide for an exhaustive list of costs that may be considered by Arbitral Tribunals when ruling on costs.[1]

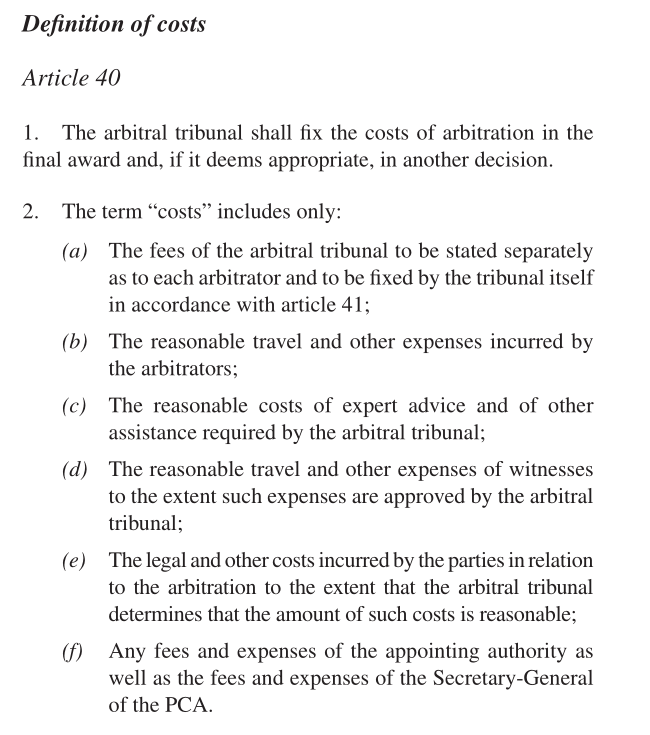

Article 40 of the Rules provides that the recoverable costs of arbitration include legal and other costs incurred by the parties to the extent that the arbitral tribunal determines that these costs are reasonable:[2]

Although an entitlement to recover in-house costs is not explicitly provided by Article 40 of the Rules, the term “other costs” is interpreted to include costs of in-house counsel, management and other costs referred to as in-house costs.[3]

The 2016 UNCITRAL Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings explicitly acknowledge that in-house costs may represent a large portion of a party’s costs when in-house counsel, and other employees, are involved in arbitral proceedings and provides for the discretion of arbitral tribunals to order their recovery:[4]

While it is widely accepted that costs incurred by the parties in respect of legal representation, witnesses and experts are recoverable, most arbitration rules are silent on internal legal, management and other costs (referred to as “in-house costs”) that parties may incur in pursuing or defending arbitral claims, leaving the issue of their recoverability to the discretion of the arbitral tribunal. Such in-house costs may represent a large portion of a party’s total costs when in-house counsel, managing directors, experts and other staff members take a proactive role before and during the arbitral proceedings. There is no principle prohibiting the recovery of in-house costs incurred in direct connection with the arbitration.

Accordingly, in principle, in-house cost may be recovered to the extent reasonably incurred by the parties.

Conditions for the Recovery of In-House Costs

The Oxford Commentary on UNCITRAL Rules provides that any request for costs must be supported and evidenced, and a failure to evidence the claimed costs may result in no award of compensation:[5]

A request for costs, like any claim before the arbitral tribunal, must be supported by sufficient evidentiary documentation to satisfy the burden of proof. Such documentation permits the arbitral tribunal to apportion and award costs meaningfully by establishing an accurate baseline of actual incurred costs. Sufficient proof of costs […] should include an adequate and itemized description of the tasks performed and the relevant billing rates. Failure to document claims sufficiently may result in no award of compensation.

Additionally, the 2016 UNCITRAL Notes on Organizing Arbitration Proceedings provides that consideration of in-house costs relating to in-house counsel and employees, is subject to a number of conditions:[6]

There is no principle prohibiting the recovery of in-house costs incurred in direct connection with the arbitration. Some arbitral tribunals have awarded such costs insofar as they were necessary, did not unreasonably overlap with external counsel fees, were substantiated in sufficient detail to be distinguished from ordinary staffing expenses and were reasonable in amount.

In ICC arbitration, it is also settled that whenever parties fail to sufficiently substantiate and prove the in-house costs claimed, reimbursement should be refused.[7]

Accordingly, an arbitral tribunal may award in-house costs claimed by parties, if the claiming party demonstrates that these costs are (1) incurred in direct connection with this arbitration; (2) that they were necessary; (3) that they do not overlap with external counsel’s fees; (4) that they were substantiated in sufficient detail to be distinguished from ordinary staffing expenses; and (5) that they were reasonable.[8]

Proving In-House Costs

Evidencing and determining the time spent and work done by in-house counsel and/or other employees is sometimes difficult.[9]

In this respect, timesheets recording the activity and time spent by in-house lawyers will be required for substantiating and evidencing in-house costs.[10]

Additionally, an accurate rate of cost entitlements must be established.[11] To determine the rate of such a cost entitlement, calculations may need to be based on salary including overheads. Any calculations made based on similar external charges would not reflect the true cost incurred.[12]

In this respect, an arbitral tribunal may impose higher substantiation requirements where in-house counsel are concerned.[13]

Separately, the ICC Commission Report on Costs also affirmed that when parties fail to sufficiently substantiate and prove in-house costs claimed, their reimbursement was generally refused.[14]

Conclusion

In principle, reasonable in-house costs may be recovered in UNCITRAL arbitrations. Arbitral tribunals have discretion to consider such costs whenever reasonably incurred. However, the establishment of these costs may be difficult. In this respect, parties should consider recording and evidencing the time incurred by employees, management and in-house counsel in direct relation to arbitrations, from their very outset. Additionally, parties should seek to establish accurate rates for these costs.

[1] D. Caron, L. Caplan, The UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, A Commentary, (2nd Ed.) p. 777.

[2] UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules Art. 40.

[3] C. Baltag, In-House Counsel and Recoverability of Costs in International Arbitration: Time for a Clear-Cut Position? in S. Tung et al. (eds), Finances in International Arbitration: Liber Amicorum Patricia Shaughnessy, (Kluwer Law International 2019) pp. 1 – 12.; UNCITRAL, Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings (2016).

[4] UNCITRAL, Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings, (2016) para. 40.

[5] David Caron, Lee Caplan, Oxford Commentaries on International Law, The UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules (Second Edition, 2013), 4. Apportionment of Costs, Article 42.

[6] UNCITRAL, Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings, (2016) para. 40.

[7] C. Baltag, In-House Counsel and Recoverability of Costs in International Arbitration: Time for a Clear-Cut Position? in S. Tung et al. (eds), Finances in International Arbitration: Liber Amicorum Patricia Shaughnessy, (Kluwer Law International 2019) pp. 1 – 12.; UNCITRAL, Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings, (2016) para. 1.04.

[8] UNCITRAL Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings, (2016) para. 40.

[9] M. Bühler, The Guide to Damages in International Arbitration, Global Arbitration Review; C. Baltag, In-House Counsel and Recoverability of Costs in International Arbitration: Time for a Clear-Cut Position? in S. Tung et al. (eds), Finances in International Arbitration: Liber Amicorum Patricia Shaughnessy, (Kluwer Law International 2019) para. 1.04.

[10] M. Bühler, The Guide to Damages in International Arbitration, Global Arbitration Review; See also, J. Waincymer, Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration, (Kluwer Law International 2012) pp. 1191 – 1262.

[11] J. Waincymer, Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration, (Kluwer Law International 2012) pp. 1191 – 1262.

[12] J. Waincymer, Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration, (Kluwer Law International 2012) pp. 1191 – 1262.

[13] J. Waincymer, Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration, (Kluwer Law International 2012) pp. 1191 – 1262.

[14] C. Baltag, In-House Counsel and Recoverability of Costs in International Arbitration: Time for a Clear-Cut Position? in S. Tung et al. (eds), Finances in International Arbitration: Liber Amicorum Patricia Shaughnessy, (Kluwer Law International 2019) pp. 1 – 12. ; UNCITRAL, Notes on Organizing Arbitral Proceedings, (2016) para. 1.04.