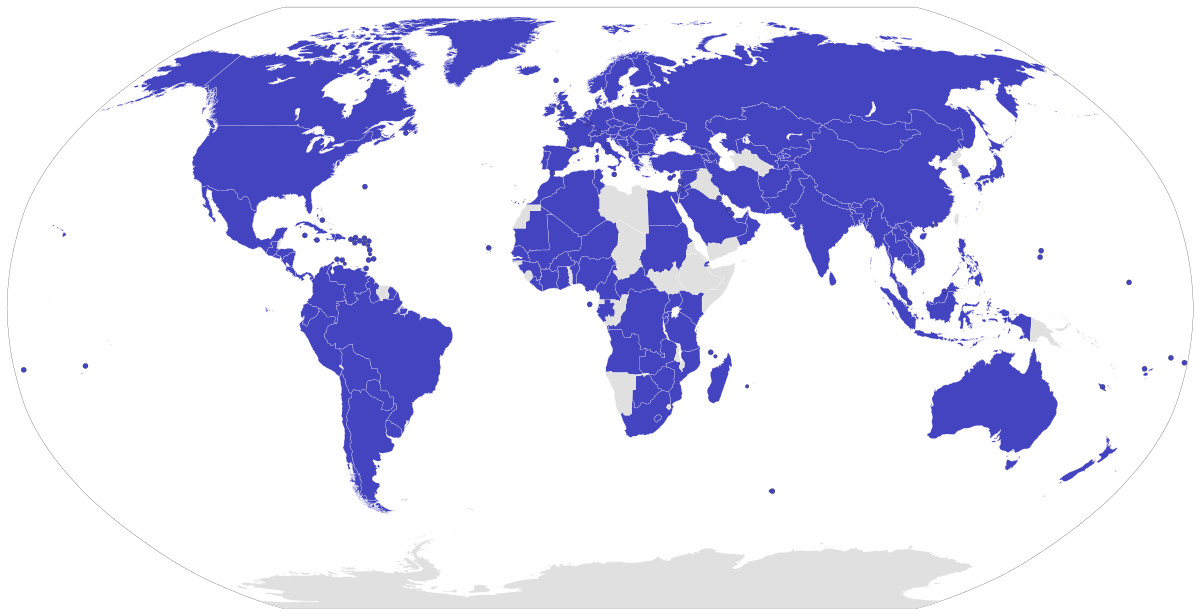

The New York Convention compels its 157 contracting Parties to enforce arbitration awards: “A New York Convention award may, by leave of the court, be enforced in the same manner as a judgment or order of the court to the same effect”.

This enforcement requirement, found in Section 101 of the Arbitration Act 1996, is however not without limitations. For example, Section 103(3) states: “recognition or enforcement may be refused if such recognition or enforcement would be contrary to public policy.”

How do English Courts approach arbitration awards tainted by fraud? Does any element of fraud engage the public policy exception? Specifically, do English Courts use their discretion to refuse the enforcement of such an award? These questions will be the focus of this article.

Sinocore v RBRG[1]

A High Court decision from 2017 has reaffirmed the reluctance of English Courts to restrict the enforcement of arbitral awards.

Background

The dispute arose from a contract for the sale of goods. The buyer (RBRG) prevented the seller (Sinocore) from obtaining payment under a letter of credit (L/C). It did so after Sinocore provided the bank with a fraudulent bill of lading (B/L), having changed the shipment period to conform to the L/C.

However, RBRG preceded this fraud by amending the shipment period on the L/C. Furthermore, Sinocore did provide RBRG with accurate documents. Nonetheless, RBRG terminated the contract and commenced a CIETAC arbitration against Sinocore. The award was rendered in Sinocore’s favour.

As summarised by the Court: “Sinocore had not agreed to the revised shipment date, RBRG was in breach of the Sale Contract in procuring that Rabobank amended the Letter of Credit so that it was inconsistent with the terms of the Sale Contract in that regard. It was this breach of contract, the Tribunal found, which resulted in Sinocore not receiving payment and caused the termination of the Sale Contract and losses to be incurred.”[2]

Enforcement Found not Contrary to Public Policy

RBRG sought to have the award set aside on the basis of Section 103(3) (“Recognition or enforcement of the award may also be refused if the award is in respect of a matter which is not capable of settlement by arbitration, or if it would be contrary to public policy to recognise or enforce the award.”) The court, however, did not entertain the argument of RBRG that enforcing the award would be contrary to public policy.

RBRG contended that enforcement would “assist a seller who presented forged documents under a letter of credit”. It argued that letters of credit “are the lifeblood of international commerce”[3] and quoted Lord Diplock who stated that: “… The exception for fraud on the part of the beneficiary seeking to avail himself of the credit is a clear application of the maxim ex turpi causa non oritur actio or, if plain English is to be preferred, ‘fraud unravels all’. The courts will not allow their process to be used by a dishonest person to carry out a fraud. [4]” [5]

The Court considered that the fraud exception refers to the bank’s strict duty to pay under a letter of credit. The scope of its applicability, however, does not prevent a party who presents fraudulent documents from obtaining relief more generally.[6] Furthermore, the Court found it inappropriate to scrutinise the tribunal’s analysis of the facts or the way it applied Chinese law.[7] It opined that there is a significant public interest in the finality of international arbitration awards, which in this case, “clearly and distinctly” outweighs the issue of fraud.[8]

When Will Fraud Prevent Enforcement in English Courts?

A contract’s inherent illegality will trigger the public policy exception. In other words, it is not the conduct of the parties that is important, but the nature of the contract itself. For example, English courts have refused to enforce an award that concerned a contract to smuggle carpets[9]. This was because enforcing the award would be giving effect to a contract that is contrary to English public policy.

In this case, the Court stressed, “we are dealing with a judgment which finds as a fact that it was the common intention to commit an illegal act, but enforces the contract”[10].

Essentially, English Courts are not prepared to recognise awards that were made on the basis of a relaxed approach to illegality. This is where the public policy exception is applicable. The scope of its applicability is otherwise quite narrow. Awards merely tainted by evidence of fraud do not generally fall within the scope of this exception.

[1] Sinocore International Co. Ltd. v RBRG Trading (UK) Limited [2017] EWHC 251 (Comm).

[2] Ibid para. 18(2)

[3] Statement supported by Lord Denning M.R. in Edward Owen v Barclays Bank International Ltd. [1978] QB 159, para. 171D

[4] UCM v Royal Bank of Canada [1983] 1 AC 168, para 184A

[5] Supra n1, para. 23(2)

[6] Ibid, para. 46

[7] Ibid, para 44

[8] Ibid, pars 47

[9] Soleimany v Soleimany [1999] QB 785

[10] Ibid, para. 33