Investment arbitration, like any arbitration, is a creature of contract. A party submitting a case to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (the “Centre”) therefore must ensure that their adversaries have consented to arbitrate. This article answers the ‘what, how, and when’ of consent in investment arbitration.

What is “Consent”?

Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention establishes “consent” to submit disputes to the Centre:

The jurisdiction of the Centre shall extend to any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment […] which the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Centre.[1]

Because the form of consent is open-ended under the Convention, three methods to perfect consent have arisen: via contract, via domestic legislation or via treaty.

Consent by Contract

For contracts, the wording must incorporate a clear minimum level of consent which covers the scope of the dispute under the ICSID.[2] Not all arbitration agreements need to be in one document, however. In fact, many tribunals have upheld consent by relying on a network of related agreements, some of which did not contain an arbitration clauses.[3] Thus, the focus is not on the way a document appears but rather how it reads in the context of the parties’ overall relationship.

Consent Through National Legislation

Another way in which host States are often bound to arbitrate is through its national legislation, including investment codes and similar legislation. Like a contract’s wording, the parties must unequivocally agree to arbitrate; invitational language such as “may also agree” is inadequate.[4]

Consent by Treaty

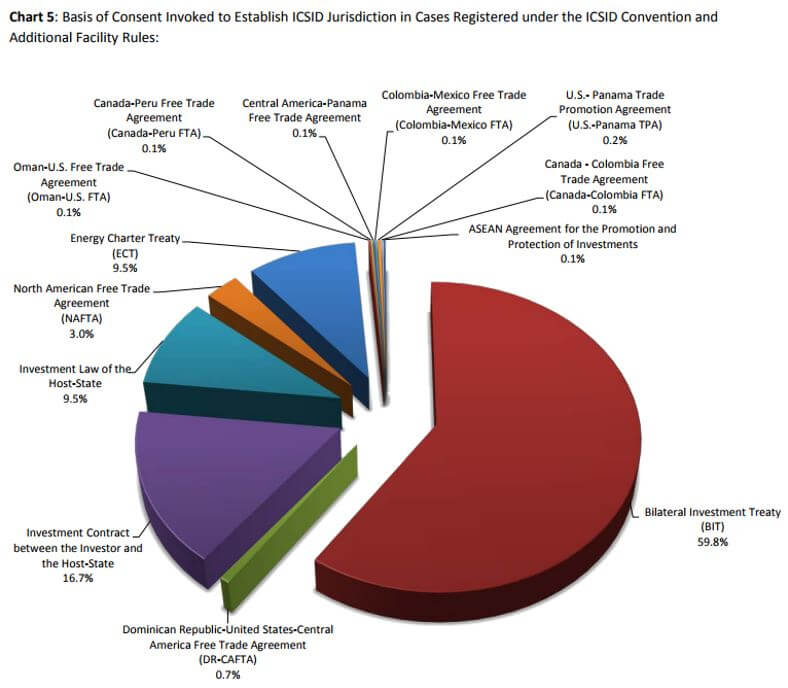

The third method of consent is under an international treaty, often in the form of a bilateral investment treaty (“BIT”). This approach offers investors the right to arbitrate many disputes arising from a wide range of public authorities even if no specific agreement has been concluded.[5] As the graph below shows, this is the most popular method of perfecting consent:

Scope of Consent

The scope of consent is also essential. A State is free to limit its consent to specific issues, such as the amount of compensation for an expropriation[7] or disputes over natural resources only.[8]

Investors must also consent to the arbitration. Unlike traditional contractual arrangements, where consent is implied by the parties’ agreement, the investor can perfect consent either by bringing a claim (e.g., filing a Request for Arbitration) or providing notice via a ‘trigger’ letter prior to filing.

Importantly, the date of filing impacts certain timing factors, including the investor’s nationality, the irrevocability of either party’s consent,[9] and the exclusion of other available legal remedies.[10]

Conditions to Consent

Before kick-starting the arbitration, investors should be aware of the various pre-conditions that may limit consent.

The first condition is waiting (or ‘cooling off‘) periods. These generally require parties to engage in settlement negotiations over a certain period, often for six months. Cases have been split, however, on characterising this pre-dispute requirement as a jurisdictional[11] issue or merely a procedural one.[12]

An investor can bypass this issue by including in its trigger letter its good-faith willingness to seek a resolution with State agents and resending the letter later (indicating its good-faith efforts to reach a settlement) should it not receive a response.

Many BIT’s also contain ‘fork-in-the-road’ clauses. In short, if a party chooses arbitration over local litigation, then a tribunal will preclude the latter according to res judicata principles. Notably, administrative proceedings may not amount to local litigation depending on the treaty’s language.

Moreover, unlike under general public international law, a party does not typically need to exhaust local remedies unless specified.[13]

If a BIT requires domestic litigation, former cases have raised an interesting question: can investors avoid pre-conditions through most-favoured-nation (‘MFN’) clauses to establish consent?

Tribunals and practitioners are strongly divided on the issue.[14] The specific treaty language is critical. A few cases have held that consent cannot arise through another treaty unless the MFN language clearly and undoubtedly intends to incorporate it.[15]

Withdrawal from the ICSID Convention and Issues of Consent

In the last decade, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela denounced the ICSID Convention.[16] Because of a six-month interim period between written notice and denunciation taking effect, claimants were able to file post-notice under applicable BIT’s.

However, there are two competing theories of consent in such instances. In the first case, consent is bilateral, requiring (1) a BIT offer of consent and (2) acceptance via a Request for Arbitration or trigger letter. The second theory merely requires a State’s consent in the BIT, which cannot be revoked and is unaffected by denunciation.

[1] ICSID Convention, Art. 25(1).

[2] E.g., ICSID Model Clause.

[3] This is common with concession and licensing contracts as well as financial guarantees and investments.

[4] See, e.g., ConocoPhillips v. Venezuela.

[5] See generally J. Paulsson, “Arbitration Without Privity,” 10 Foreign Investment Law Journal 2, Fall 1995.

[6] ICSID Caseload Statistics Issue 2017-1.

[7] Franz Sedelmayer v. Russia.

[8] E.g., Ecuador (4 December 2007).

[9] ICSID Convention, Art. 25(1).

[10] ICSID Convention, Arts. 26 and 27(1).

[11] E.g., Burlington Resources v. Ecuador; Goetz v. Burundi.

[12] E.g., Lauder v. Czech Republic; Biwater Gauff v. Tanzania.

[13] ICSID Convention, Art. 26.

[14] Compare Maffezini v. Spain and Wintershall v. Argentina.

[15] Plama v. Bulgaria; Salini v. Jordan; Telenor v. Hungary.

[16] ICSID Convention, Arts. 71 and 72.