ICSID arbitration refers to arbitral proceedings conducted under the aegis of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (the “ICSID Centre”), established by Article 1 of the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (the “Convention”), which entered into force on 14 October 1966. The Convention provides for the settlement of disputes between foreign investors and host States by way of arbitration or conciliation, which are administered by the ICSID Centre.

The Convention was formulated by the Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, an arm of the World Bank. The purpose was to create an instrument of international cooperation and economic development, encouraging foreign investment.

The initiative began in 1961, when the General Counsel of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Mr. Aron Broches, sent a note to the World Bank’s Executive Directors containing his main ideas for the Convention. Mr. Broches’ proposal was approved and presented by the President of the World Bank in its Annual Meeting in Vienna, on 19 September 1961. From Mr. Broches’ initial ideas, it took almost five years for the release of the first Revised Draft of the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States in December 1964.

ICSID arbitration serves a purpose. States that have ratified the Convention offer a more friendly environment to foreign investors and may attract more international investment as a result. In addition, host States of investment protect themselves against diplomatic claims. On the other hand, foreign investors have access to a unique international forum, providing a measure of security for foreign investment decisions.

The First ICSID Arbitration Cases

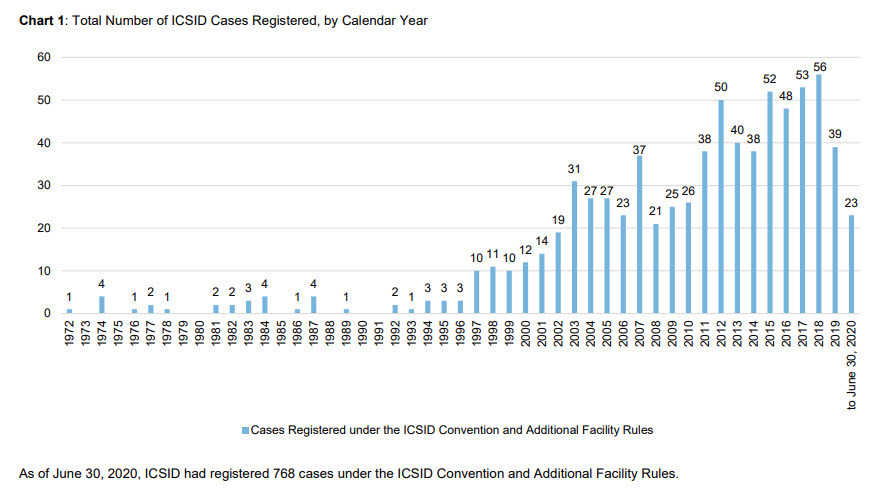

In the early years of the ICSID, the Centre’s dispute settlement procedures were seldom used. Nevertheless, over the years, the number of ICSID arbitrations has increased significantly.

Today, the ICSID website lists 163 signatory and contracting States.[1] Additionally, several bilateral investment treaties (“BITs”) currently provide for dispute settlement under the Convention, some multilateral treaties also allow ICSID dispute settlement to investors, and the domestic legislation on foreign investment of a number of countries permit ICSID arbitration to foreign investors in the event of a foreign investment dispute arising.

For the ICSID, the first case brought under a BIT was AAPL v. Sri Lanka.[2] The treaty had been entered between the United Kingdom and Sri Lanka in 1980, providing an early example of ICSID dispute resolution provisions in BITs:

Article 8

Each Contracting Party hereby consents to submit to the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (herein referred to as “the Centre”) for settlement by conciliation or arbitration under the Convention […] any legal disputes arising between that Contracting Party and a national or company of the other Contracting Party concerning an investment of the latter in the territory of the former.

In AAPL v. Sri Lanka, claimant’s investment was destroyed in January 1987 during a military operation in Ski Lanka. The arbitral tribunal ruled for the first time that, in the absence of a provision on applicable law in the UK-Sri Lanka BIT, the BIT was the primary legal source and Sri Lankan domestic law was a supplementary source:[3]

Effectively, in the present case, both Parties acted in a manner that demonstrates their mutual agreement to consider the provisions of the Sri Lanka/UK Bilateral Investment Treaty as being the primary source of the applicable legal rules.

The first ICSID award on the merits dated from 1977, however. On 29 August 1977, the arbitral tribunal formed by Pierre Cavin, Jacques Michel Grossen and Dominique Poncet issued an award in favor of an Italian investor in Adriano Gardella S.p.A. v. Côte d’Ivoire,[4] which was based on a 1970 Agreement providing for disputes relating to the conversion and cultivation of 20,000 hectares of and for the construction of a textile factory to be resolved via ICSID arbitration.

Also, five years earlier, in 1972, an arbitral tribunal had issued the very first decision of the ICSID: the granting of provisional measures in Holiday Inns v Morocco, in an arbitration which was later discontinued in 1978.[5] Pierre Lalive, who founded the law firm Lalive in Geneva, notably served as counsel.

Obtaining Jurisdiction in ICSID Arbitration

The general rules of substantive jurisdiction are regulated by Article 25 of the Convention.

The procedure for the determination of ICSID jurisdiction is provided in Article 36(3), which includes the Secretary-General’s power to register a request for arbitration, unless a dispute is manifestly outside the jurisdiction of the Centre.

Article 36(3)

The Secretary-General shall register the request unless he finds, on the basis of the information contained in the request, that the dispute is manifestly outside the jurisdiction of the Centre. He shall forthwith notify the parties of registration or refusal to register.

Article 25 of the Convention specifies the requirements ratione materiae (regarding the nature of the dispute) and ratione personae (regarding the parties to the dispute). The former provides that the dispute must be of a legal nature and arise directly from an investment, whereas the latter requires the parties to be a contracting State and a national of another contracting State.

Article 25(1)

The jurisdiction of the Centre shall extend to any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment, between a Contracting State (or any constituent subdivision or agency of a Contracting State designated to the Centre by that State) and a national of another Contracting State, which the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Centre. When the parties have given their consent, no party may withdraw its consent unilaterally.

For the purpose of ICSID jurisdiction, the date on which the proceedings were commenced is crucial. All the requirements for jurisdiction must be fulfilled on the day the proceedings are instituted. As a result, events that take place after the date of commencement do not affect the Centre’s jurisdiction.[6]

In CSOB v. Slovakia, claimant assigned its rights against respondent to the Czech Republic, but Slovakia argued that such an assignment would halt tribunal jurisdiction under Article 25(1) of the Convention. The arbitral tribunal rejected the argument on the basis that the assignment took place after the filing of the request and noted that the relevant date for the purpose of ICSID jurisdiction is the date on which the proceedings were instituted:[7]

It is generally recognized that the determination whether a party has standing in an international judicial forum for purposes of jurisdiction to institute proceedings is made by reference to the date on which such proceedings are deemed to have been instituted.

Another crucial aspect of ICSID jurisdiction is the definition of “investment”. The Convention is silent as to the scope of “investment” and its determination is left to the parties. During the Convention’s negotiations, although a group recommended the inclusion of a descriptive list, it was understood that a definition would create jurisdictional difficulties in a case-by-case analysis.

Nonetheless, the definition of “investment” is perceived as an objective one. Most tribunals in ICSID arbitrations apply a dual test in order to determine if the activity in question constitutes an investment in accordance with the Convention’s requirements. If jurisdiction is based on a BIT, the definition of investment in the BIT is relevant. Additionally, the arbitral tribunal will analyze if the activity is an investment within the meaning of the Convention. This double test became known as the “double-barreled” test

Fedax v Venezuela was the first ICSID case in which the Centre’s jurisdiction was challenged on the basis of nonfulfillment of the term “investment” pursuant to the Convention. The dispute arose due to the non-payment of promissory notes by Venezuela. Venezuela challenged the Centre’s jurisdiction on the ground that the acquisition of promissory notes, as a loan, would not constitute an investment for the purpose of the Convention and the relevant BIT. The arbitral tribunal rejected the argument, noting that “under both ICSID and the Additional Facility Rules the investment in question, even if indirect, should be distinguishable from an ordinary commercial transaction”.[8]

Regarding jurisdiction ratione personae, the Convention expressly excludes dual nationals from initiating ICSID arbitration (Article 25(2)(a)):

Article 25

(2) “National of another Contracting State” means:

(a) any natural person who had the nationality of a Contracting State other than the State party to the dispute on the date on which the parties consented to submit such dispute to conciliation or arbitration as well as on the date on which the request was registered pursuant to paragraph (3) of Article 28 or paragraph (3) of Article 36, but does not include any person who on either date also had the nationality of the Contracting State party to the dispute;

Therefore, an individual who holds the nationality of two contracting States to the dispute cannot bring a claim under the ICSID Convention (but may potentially do so under other arbitration rules).

The issue of dual nationality was debated extensively during the Convention’s negotiations. Eventually, the proposal to exclude dual nationals was accepted, if one nationality is that of the host State. Today, the requirement of nationality is an objective criterion that is determined in addition to the investor’s consent to ICSID arbitration and ascertained in accordance with the laws of the State whose nationality is claimed.

In Micula v. Romania, Romania argued that the claimants’ Swedish nationality was not relevant given claimants’ effective ties to Romania. The tribunal did not accept this and noted that the claimant held just Swedish nationality.[9] It is debatable, and has been debated, whether the notions of “genuine” and “effective” nationality are applicable to ICSID arbitration.

Article 25(2) also deals, less strictly, with the nationality of juridical persons:

Article 25

(2) “National of another Contracting State” means:

(b) any juridical person which had the nationality of a Contracting State other than the State party to the dispute on the date on which the parties consented to submit such dispute to conciliation or arbitration and any juridical person which had the nationality of the Contracting State party to the dispute on that date and which, because of foreign control, the parties have agreed should be treated as a national of another Contracting State for the purposes of this Convention.

Thus, companies, with foreign control, incorporated in the host State, may have access to ICSID Arbitration. For instance, in Aguas del Tunari v. Bolivia, brought under the Netherlands-Bolivia BIT, although claimant was incorporated in Bolivia, the ICSID tribunal upheld jurisdiction on the basis that control was vested in Dutch hands, which held 55% of claimant’s shares.[10]

Costs of ICSID Arbitration

The costs of an ICSID Arbitration primarily consist of:

- costs for the use of the facilities and the Centre’s expenses, including a non-refundable lodging fee of USD 25,000 paid by the party initiating the proceedings, as well as an annual administrative charge of USD 42,000 (which pays for a case team and financial management);

- arbitrators’ fees of USD 3,000 per day of meetings or other work performed; and

- expenses incurred by the parties related to the proceedings, including the cost of legal representation and expert fees.

Typically, costs of legal representation represent the largest head of costs for ICSID arbitration. Actual costs of an ICSID arbitration depend on several aspects, however, such as the complexity of the case, the number of arbitrators, the amount in dispute, the duration of the proceedings, the number of hearing sessions and the legal team involved.

The Convention does not provide substantive guidance as to the criteria that arbitral tribunals should follow in determining how parties must bear their costs. Some decisions suggest that a “costs follow the event” or “loser pays” approach has considerably increased over the years. For instance, in applying a “costs follow the event” approach, the arbitral tribunal in Southern Pacific Properties (Middle East) Limited v. Arab Republic of Egypt considered that claimant should be reimbursed for the legal fees it had incurred as part of its compensation:[11]

In a case such as the present one, where the measure of compensation is determined largely on the basis of the out-of-pocket expenses incurred by the claimant, there is little doubt that the legal costs incurred in obtaining the indemnification must be considered as part and parcel of the compensation.

In EDF v. Romania, “costs follow the event” allocation was also considered as an alternative to splitting costs evenly:[12]

But the investment arbitration tradition of dividing the costs evenly may be changing, although it is a bit early to know whether a different approach is evolving […]. That is, there should be an allocation of costs that reflects in some measure the principle that the losing party pays, but not necessarily all of the costs of the arbitration or of the prevailing party.

In a more recent case, Blue Bank International v. Venezuela, the arbitral tribunal also made reference to “an increasing trend to acknowledge that a successful party should not normally be left out of pocket in respect of the legal costs reasonably incurred in defending its legal rights”.[13]

ICSID Arbitration Statistics

In August 2020, the Centre released the ICSID Caseload – Statistics (Issue 2020-2) based on the cases registered by the Centre as of 30 June 2020 under the Convention and under the Additional Facility Rules.

ICSID Statistics reveal that in the first semester of 2020, 22 arbitrations were admitted by the Centre. Amongst the cases registered, 26% involved parties from Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 23% from South America, and 15% from sub-Saharan Africa.

With regard to economic sectors, the majority of cases involve investments in the Oil, Gas & Mining Sector, followed by Electric Power & Other Energy. Cases also concerned, however, Transportation, Construction, Finance, Information & Communication, Water, Sanitation & Flood Protection, Agriculture, Fishing & Forestry, Tourism and Services & Trade.

Finally, 74% of the cases were based on BITs, whereas 11% were based on Investment Contracts between the investor and the host State.

[1] Belize, Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Kyrgyz Republic, Namibia, Russia Federation and Thailand are signatory States only.

[2] Asian Agricultural Products Ltd. (AAPL) v. Sri Lanka, Case No. ARB/87/3, Award dated 27 June 1990.

[3] Asian Agricultural Products Ltd. (AAPL) v. Sri Lanka, Case No. ARB/87/3, Award dated 27 June 1990, ¶ 20.

[4] Adriano Gardella S.p.A. v. Côte d’Ivoire, ICSID Case No. ARB/74/1, Award dated 29 August 1977.

[5] Holiday Inns S.A. and others v. Morocco, ICSID Case No. ARB/72/1, Decision on Provisional Measures dated 2 July 1972.

[6] The term “jurisprudence constante” was developed by the International Court of Justice in Democratic Republic of Congo v. Belgium.

[7] Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka, A.S. v. The Slovak Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/97/4, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction dated 24 May 1999, ¶ 31.

[8] Fedax N.V. v. The Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/96/3, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction dated 11 July 1997, ¶ 28.

[9] Ioan Micula, Viorel Micula, S.C. European Food S.A, S.C. Starmill S.R.L. and S.C. Multipack S.R.L. v. Romania [I], ICSID Case No. ARB/05/20, Decision on Jurisdiction dated 24 September 2008, ¶ 106.

[10] Aguas del Tunari v. Bolivia, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3, Decision on Jurisdiction dated 21 October 2005, ¶ 317.

[11] Southern Pacific Properties (Middle East) Limited v. Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/84/3 Award on the Merits dated 20 May 1992, ¶207.

[12] EDF (Services) Limited v. Romania, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/13, Award dated 8 October 2009, ¶¶325-327.

[13] Blue Bank International & Trust (Barbados) Ltd. v. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB 12/20, Award dated 26 April 2017, ¶207.